- Home

- Leadership

- Staff Management

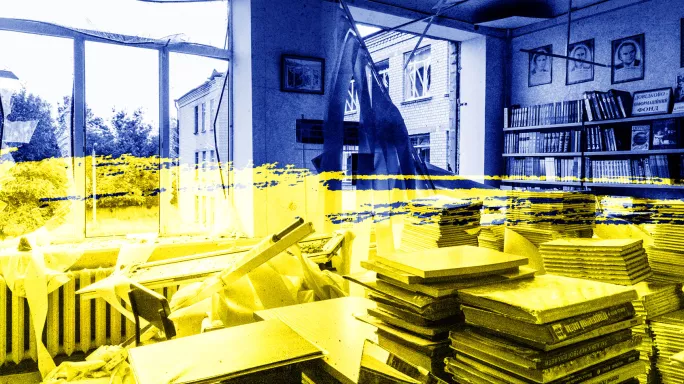

- Education in a war zone: a year in a Ukrainian school

Education in a war zone: a year in a Ukrainian school

There was novelty value at first, but now the children hear the warning, walk in line and are escorted out of classrooms by their teachers.”

David Cole - headteacher at the British International School, Ukraine (BISU) - is not describing a fire drill. Instead, he’s describing what happens when the air-raid siren goes off during the school day, warning of an incoming Russian missile strike against Kyiv.

Cole is speaking on Zoom, his calm and friendly body language set against a colourful virtual background that he’s chosen. In a sense, this is the thrust of his work: to curate a backdrop of normality, of today being just a normal day, of BISU being just another everyday school.

It is anything but. Indeed, just 15 minutes before the interview, staff and students at the school were in the air-raid shelter in the basement of the Kyiv campus.

Even when they are in the shelter, though, education comes first, Cole explains. “It’s like a huge classroom. There are tables and chairs and wi-fi, and at one end of the room you’ll have your early years and at the other you’ll have your sixth form,” he says.

“The air-raid warning goes off and students take their laptops and basically just get on with it.”

Schools in Ukraine: terror and defiance

The pressures that Cole and his staff - and, indeed, all teachers in schools across Ukraine - are experiencing are completely extraordinary.

Air raids are unpredictable. At the start of the conflict, the citizens of Kyiv were getting a warning of four or so minutes before missiles struck. Now, with Russia employing more sophisticated weaponry against them, that warning time has been reduced to just two. Russia, as has been widely reported, has been targeting key infrastructure.

“We’ve got blankets in the shelter,” Cole says, matter of factly. “There are chemical toilets, emergency LED lighting, food and medical provisions so that, should something terrible happen, we could stay there for a number of days.”

Just over a year ago, the threats that Russia was making of an all-out invasion were widely seen to be little more than sabre rattling. Now, on the anniversary of that invasion (24 February), educators across Ukraine live with the war as a relentless background to their daily lives.

Yet, amid all the carnage and terror, schools such as BISU have maintained education - not just to ensure that pupils have a sense of normality in their own day-to-day lives but also to play their part in the cultural resistance to Russia’s war aims.

“Russia is trying to eradicate Ukrainian language and culture. They are trying to remove internationalism and multiculturalism and replace it with some kind of sterile, brainwashing-type curriculum,” Cole says. “So we do see education as part of the resistance, as one of the ways that will help this community get through this war.”

This means maintaining education, and ensuring that students get the most out of their education and have a future of hope and prosperity.

‘We see education as part of the resistance. It will help this community get through this war’

Of course, some BISU pupils have left, and some now only access lessons remotely. But many others remain in Ukraine because they have family there or because they simply cannot afford to leave.

Whatever the situation, the school’s focus is on the next steps for pupils.

“For our older students, their main concern is their GCSEs. Then we also have sixth-formers studying for their International Baccalaureate and looking to next year to think about their options,” says Cole.

“Once the war is won, there will still be a prolonged period as students gradually return, so it is absolutely crucial that we continue to plan for a well-organised, high-quality offering so that students can build back towards normality as soon as possible.”

This is why learning continues in air-raid shelters.

BISU has a sister school in Dnipro, in the south-east of the country, much closer to the front line.

The head there is Veronika Efimenko. Speaking to Tes through a translator, she exudes a defiance in the face of war that education must continue.

“The city experiences a little bit of a harder time than Kyiv, and there are more air-raid alerts. But everyone is prepared for that, and they know the drill,” she says.

“Within two minutes, the whole school is already in the shelter, with everything that they need for the learning process. There is wi-fi. The generator is working. Education goes on.”

Life on the front line

Yet Efimenko acknowledges that there is no pretending that things are normal when missiles rain down. The impact on the pupils is emotionally and mentally draining - something the school seeks to tackle where it can.

“Sometimes, even in the shelter, we hear loud explosions,” she explains. “So it is very important for the staff not only to be prepared in terms of the air-raid drill but also to provide a secure environment for children.

“That’s why in school we employ a skilled counsellor, Daria, who can offer help to overcome all this stress and anxiety.”

More on the Ukraine war:

- Fleeing a war zone but teaching goes on

- Running a school in a war zone - life as a head in Ukraine

- What I did today when students asked about Ukraine

This professional help is also on hand for teachers, something she says has been vital to help them navigate this horrendous time.

“Daria has been crucial for teachers taking advantage of the opportunity to meet and talk with her, just to know that that ‘emotional safety net’ is there,” Efimenko explains.

“She has also organised CPD for staff related to personal mental health, identifying when a problem may be emerging and how to provide support for others.”

Help for both schools - moral support and leadership input, as well as material help - has come from all over the world.

“Cobis [the Council of British International Schools] and the Black Sea Schools Group [a group compromised of international schools in this geographic area] have provided incredible support,” says Cole.

“These partner schools have been supporting us to expand our range of subject options at GCSE and A level.”

International support

Another school Cole praises is City of London Freemen’s School, explaining that it has provided students at BISU with access to its enrichment programme. This is a whole afternoon each week when students can focus on personal development, leadership and communication skills.

“The quality of support that they have been offering students with their exam subjects has been incredible, and crucial,” Cole says.

He also applauds the work of examination boards in helping BISU students as another example of the education sector coming together to show its strength and support.

“The International Baccalaureate organisation has been very supportive, as have examination bodies like Cambridge, putting in place special arrangements for students in Ukraine so that they can submit portfolios of work rather than having to rely on terminal papers,” Cole explains.

‘There is wi-fi. The generator is working. Education goes on’

Cole and Efimenko are also working with Ukrainian universities to get them to accept the IB as an entrance qualification. “That is partly selfish because it’s part of drawing Ukraine more into becoming a European nation,” says Cole.

And as part of engaging with other organisations, the school has even found time for a bit of fun. “We’ve made new connections with the Global School Alliance,” Cole explains, “and are working in collaboration with Liverpool Life Sciences UTC to do something to commemorate the Eurovision Song Contest being held in Liverpool.”

That all this - teaching, assessment, university applications, school outreach work - has been retained for students in a country at war is testament to the staff who have remained committed to their schools.

Of course, many of the international staff are doing their work remotely - something Cole says is safer for everyone.

“To have lots of international staff here in person at this time, to be honest, would have been a burden. We have a duty of care as an employer and we are limited in how much care we can offer,” he says.

Not that having staff working in other countries makes things easy: Cole admits he’s had to spend a lot of time working out the differences in time zones.

“At one point, last year, we had students and staff on every continent except Antarctica. Even now, we have staff working from the USA, UK, Germany and Georgia.”

Staff are ‘absolute heroes’

For local staff, though, such avenues of escape are often unavailable. They have remained calm in the face of the unthinkable, coming to school and ensuring that lessons are delivered.

“They are here, and they start their lessons on time,” says Efimenko. “They are absolute heroes.”

Cole is equally effusive: “We have had staff phoning in from subway stations, having had to take refuge during an air raid, apologising for being delayed on their journey to school.

“We have had staff trying to teach remote lessons from underground shelters so that children can carry on with their learning.

“That sense of continuity and commitment is so reassuring for students.”

The school has even found ways to onboard new staff to the teaching cohort; despite the war raging on, the desire to educate the next generation is undimmed.

“We are bringing on local staff so that if international staff can’t return, our programmes can go on,” Cole explains.

“The University of Sunderland has been wonderful and provided free PGCE courses for two of our teachers.”

‘Being here, you know that the war will be won’

The fact that this training has been provided underlines that in both Kyiv and Dnipro there is an unshakeable belief that the schools will continue to provide for students throughout the rest of this academic year and into the next. And so, being prepared for the future is crucial.

“We are looking to next September, too, and working hard towards that,” says Efimenko. “No one is even considering the idea of not opening for the next year.”

Cole makes a similar point: “Being here, you know that the war will be won. I did a radio interview within days of the invasion, and already Ukrainians were saying, ‘We are going to win.’ I said this to the presenter, and he asked me, ‘How do they know?’ And I said, ‘Have you ever met a Ukrainian?’”

This optimism is not blind. Both these school leaders know that any victory will be hard won, and that it will only be the beginning. The economic situation in Ukraine is a big consideration for the schools, where fees have been reduced for obvious reasons.

“We understand that [recovery] is not going to be a week,” Cole says. “It’s going to be a long time, and even once the war is won, there is still going to be a prolonged period of rebuilding as people gradually return.”

Financially, in the long term, the school may need to rely again on a wide network of support.

“We are running on about 20 per cent of our normal pupils, so the CEO and chair have made huge financial commitments, and that will be our longer-term issue: looking to expand support from other schools to ensure continuity of teaching and learning,” Cole says.

That such concerns are on the agenda underlines the belief that those in the country have of victory and a form of normality returning to their lives, and how education is central to that future.

Until then, though, the educators of Ukraine will continue to do whatever they can to provide education to the children caught up in the most awful of situations.

Cole reflects: “We smile when we see each other. We say, ‘How are you?’ Well, we’re in a war, so how well could anyone possibly be? But all we really mean is, ‘Are your loved ones safe?’”

Kester Brewin has taught in London schools for 25 years and his debut novel Middle Class is out now

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters