- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Early Years

- Why post-Covid education needs play

Why post-Covid education needs play

This article was first published on 4 October 2023

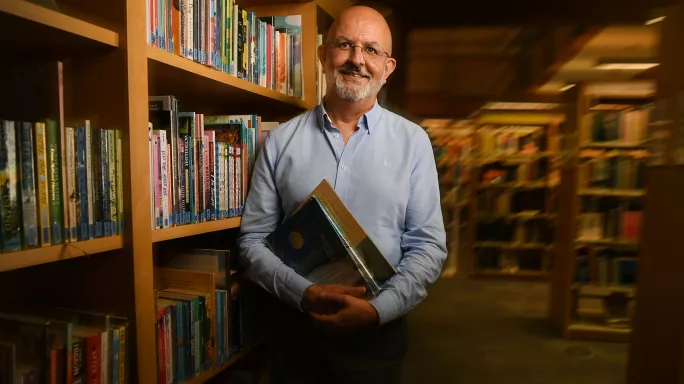

Paul Ramchandani takes play very seriously. He is the world’s first professor of play in education, development and learning, based at the University of Cambridge.

He is also director of the PEDAL Centre, which aims to study the function of play in children’s lives.

Ramchandani began his career as a child psychiatrist before moving into education, and a commitment to exploring and improving children’s wellbeing and mental health pervades his work.

His research has delved into the intricacies of family life - such as the link between children’s behaviour and play with their fathers and how paternal depression affects children - as well as critically evaluating numerous classroom interventions around social and emotional wellbeing and play.

He talks to Tes about his latest work, why making time for play could be more important after the pandemic than ever before and why a focus on the “here and now” is crucial in early years policy and practice.

You’ve dedicated much of your career to the study of play. Why is play so important?

Play is fundamental for children learning a whole ton of things.

For younger children, it’s where they learn how to communicate, to share, to interact with other children, to manage emotions when things don’t go right: a whole range of fundamental skills.

Play is a central part of most children’s lives, certainly in this country. That’s why there is a difficulty that’s arising with the kids who have come into school in the past couple of years.

I’m hearing from teachers and headteachers that, after Covid, this cohort is struggling much more with some of the rules of how to interact socially in school with peers, and also how to settle into school and settle down for work.

It’s likely that’s down, at least in part, to a lack of opportunities for play during the pandemic.

That’s why we should be so concerned about the issue of play opportunities and playtime being taken away.

A team at University College London has looked at playtimes over the past 30 years and they’ve gone down a lot.

How does having less time to play at school affect children’s ability to learn?

Children need the chance to let off steam so that they can go back in and concentrate better for their lessons.

For some children, particularly those with ADHD or very severe attention and restlessness problems, they’re able to settle much better if they’ve had a period of physical exercise.

So, getting them out and making sure they have the opportunities to let off steam will allow them to learn more effectively.

Social and emotional development is also supported by play and this, too, is fundamental - not just to later mental health and wellbeing but to children being able to learn.

If they’re in an environment where they don’t feel safe and secure and supported, their ability to learn is massively hindered, so it’s an important element of education that sometimes gets overlooked.

The risk with play diminishing in schools is that it is self-defeating.

Of course, learning stuff is really important, but if we’re not paying attention to children’s enjoyment of school and their enthusiasm for learning at some level, we’re doing them a disservice in the long run.

Ultimately, we want children as far as possible to be self-motivated.

Given the issues with attendance that many schools are now facing, how far do you think that enjoyment matters in education?

There is some interesting work that two of my colleagues, Christine O’Farrelly and Beth Barker, have undertaken: interviewing young children about how they anticipate school and what they’re excited about as they’re going into school.

It used some creative approaches to interview children, getting them to think about what’s important to them.

Those children raised a number of different things, including being excited about having the opportunity to learn, as well as the opportunity to play with friends.

But often people think that if you ask children, they’ll say they just want to play all the time.

People sometimes dismiss children’s voices, particularly those who work with older children and adolescents, assuming that they’ll just somehow skive off and ask for an easy time, and I’m sure some will.

But if you ask young children, as they’ve done in this case, they really value that they’re going to learn new stuff.

And they also value play and building relationships with peers and with teachers as an important part of their school experience.

Children do have a level of sophistication about what they anticipate as being important when you ask them, and that enthusiasm for learning is there, so we really should do everything that we can to encourage and support that.

What do we know about the value of play as a pedagogical approach in the classroom?

Last year, we published a systematic review looking at the evidence for guided play compared with other approaches to learning.

The evidence is patchy, but guided play - in which the teacher sets the aim and the goal then allows the children space to explore within that - came across as effective for learning in many areas and, in some areas of maths, was a more effective way of learning than direct instruction for young children.

That’s not to say play-based learning is the most effective for everything. It’s just that we’ve asked the question: what’s the evidence? Is it more effective, less effective?

‘Learning is important, but if we’re not paying attention to children’s enjoyment of school, we’re doing them a disservice’

And for some areas of maths - shapes and so on - there does seem to be evidence pointing towards it being more effective.

That means children being able to explore and understand things themselves within a framework set by an educator.

You’re not just saying “go to school and just play all the time with no guidance” because that’s not what school’s for.

But within the expert framework of an educator, it can be a very powerful way for children to learn in a much deeper way and a much broader, more conceptual way for some subjects.

Do you think that early education in the UK is currently focused on the right areas?

There are always tensions about where the focus should be in children’s education and early learning - whether that’s about what content they should learn, or what environment they should be in or who should be driving their learning - and there are always helpful debates to be had around that emphasis.

Recently, the focus seems to have returned to children achieving certain language outcomes.

That is really important, but we can’t neglect children’s social-emotional development as it is fundamental to their being able to learn.

Many teachers and educators are aware of this, but it’s an element of learning that is often at risk of being neglected.

It’s often teaching assistants who tend to work with children who are struggling the most in school, and they’re an increasingly highly skilled part of the workforce.

The training and support for that group of professionals is really, really important and has had a bit more attention in recent years, which I think is really welcome.

The skill involved in that role is being increasingly recognised, and hopefully will be even more as we go forward.

How can schools and other early years settings improve their approach to social and emotional learning?

It’s partly about ensuring that children’s social and emotional needs are understood and prioritised, and then fitting with that, and making sure that the management and leadership of schools are aware and getting feedback about it.

Teaching assistants are able to bring those challenges and that knowledge to the attention of teachers and to senior management as well.

Another part of the work that we’ve done, led by my colleague Sarah Baker, is to develop what’s called the Early Years Library, on the back of a research project.

The team looked at all the literature for effective early programmes and pulled out those elements that seem to be common across different effective interventions.

And then they worked with teachers to adapt those and produce a range of resources across both numeracy and literacy but also social and emotional development.

These are simple things that teachers can do around social and emotional development.

It might be about helping children to recognise and express emotions, or about communicating with others, thinking about the different ways of communicating between children.

And there are lots of other, different examples for teachers and other educators to use. It’s all about trying to take the science and implement it in everyday practice - that’s a common theme running through all our work at the centre.

You’ve recently spoken about the need for more of a ‘here-and-now’ focus in the early years in schools - what does that mean?

At the moment, early education is primarily articulated in terms of what it can do for children later down the line.

That misses some really important elements of children’s experience now, and has a tendency to focus on skills and outcomes that are about older children and adolescents - economic productivity, exams and so on - which are less appropriate when thinking about young children.

I don’t think this applies so much to teachers, because they do tend to focus on the here and now as well as the future.

But in policy terms, it’s about trying to appreciate children’s experience and what’s important to them, rather than the conversation being framed only in terms of “what will this achieve for them in 20 years’ time?”.

One of the things that we try to focus on with our research and practice is children’s perspectives and how we understand the experience of even very young children when they can’t articulate it clearly.

We look at different tools and different ways of trying to encourage children’s voices to come to the fore, sometimes using play or drawing or other kinds of materials to allow them to tell their stories.

As soon as you do that, you start to appreciate that the experience of children is different, and immediacy is very, very important to them.

Is there a way for schools to tap into the power of immediacy?

One of our research initiatives is called Playback and it is about parents, carers and teachers tuning into children’s signals and cues.

We go into parents’ homes and film them playing and interacting with their children, then we sit with the parents and go through that video and highlight the positive moments, and the children’s signals and cues.

By doing this, we can see things that you miss in everyday life because it’s busy and hectic, and you can’t notice everything.

But by slowing interactions down, you can notice the child maybe reaching out, or looking up or responding to what a parent does. And so we help parents to notice these things.

It’s an incredibly powerful intervention. We’ve done a randomised controlled trial and shown that it reduces the risk of behavioural problems in children.

‘We can’t neglect children’s social-emotional development. It is fundamental to their being able to learn’

Now we’ve adapted and developed this to work with teachers, particularly in Reception.

We use the same technique, filming teachers working with a small group of children, telling a story and then having some playtime.

Then we go back with the teacher and help them to reflect on the cues of different children and the ways they communicate, particularly those who struggle either with their behaviour or communication as they’re settling into school.

We’re at early stages with that, but it’s been positively received by the teachers.

And does that translate to full classrooms of young people?

Of course, when you’ve got 30 children, you’re doing other things and you can’t easily pay individual attention to every single child’s cues all the time.

But if you’ve got one or two children who have a more difficult time, you’re learning something about how they communicate, which might mean that you can react or manage the situation in a different way the next time.

The framing of Playback is positively focused; it isn’t telling people off for not doing the right thing, it’s equipping parents or teachers with skills to notice.

So, as a teacher, if there’s a child in your class that you’re struggling with, you learn something really important about them and the way that they do things, and that knowledge can be taken into other interactions.

The feedback from the teachers that we’ve worked with has been that it has been eye opening.

They’ve found it can improve the relationships with the children that they’re working with most closely, and also improve their skills in noticing and responding.

Zofia Niemtus is a freelance writer

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters